Over the course of the past week I've been on a bit of a zombie high. I had a pretty vivid dream where I was stuck in the middle of a zombie apocalypse, and ever since then I've been obsessed. It's gotten to the point that I'm considering writing a comprehensive article, something along the lines of The Zombie Survival Guide, that talks about how to fight zombies and survive in an infected world. It might take a while for me to get that post completed, but just for today I instead wanted to talk about all of the different zombie-related sources of media I've been ploughing through in the last week or so. If I ever do write a proper zombie post, then consider this the 'required reading' material.

I'll start with films because, to be honest, that's probably my weakest area where zombies are concerned. I have yet to see any of Romero's famous films, and I haven't seen 28 Days Later or the sequel, either. I have watched I Am Legend, but I don't really count the villains there to be 'proper' zombies, so I won't talk about that one. In fact, the two zombie films that I have seen are both satires, rather than the real deal - Shaun of the Dead and Zombieland. Of course, that's not to say that they aren't both stellar examples of the zombie genre; in fact, being able to step back and view zombies with a critical, satirical eye enables the films to use them in new, interesting ways. Shaun of the Dead is usually billed as 'a romantic comedy, with zombies'; it's the story of slacker Shaun and his good-for-nothing best mate Ed, who get caught up in a zombie apocalypse that sweeps across Britain. This is one of my favourite films of all time, and it would take a full blog post to properly do it justice. Since this is more of an overview, I'll skip over some of its other fantastic qualities - Edgar Wright's direction, the stellar main cast, etc - and focus on the zombies. Probably one of the cleverest thing that Shaun of the Dead does is points out that many people, at the moment, are not so different from zombies already. The opening montage, as the camera pans through supermarkets and car parks, shows people going through the movements of their day to day routine, lifeless, eyes half-closed, stuck in the rut of modern society. Shaun's life is just the same, as he spends every day visiting the local corner shop, going to work and then having a drink at the local pub, the Winchester. He lives the life of a zombie, never doing anything new or exciting; it's only when the dead come to life that he, too, begins to live.

The same could be said of Columbus, the protagonist of Zombieland. As a social outcast, he was never really very attached to anyone, not even his own parents. When the film begins, he is out searching for his family in a post-apocalyptic USA. Over the course of the story he meets several other wandering kindred spirits; the slightly psychopathic Tallahassee and sisters Wichita and Little Rock. By the end of the film, Columbus discovers that he has found a family, albeit not the one he was searching for; he finally has friends, people he is close to. Both this film and Shaun of the Dead show how people can change for the better when the world around them starts to fall apart; this is a recurring theme in much of the zombie media I've experienced. The stories aren't so much about the zombies as the people living amongst them, trying to survive, and how living in an undead world can affect them.

A TV show for which that principle holds true is The Walking Dead. The show start off following Rick Grimes, a sheriff who goes into a coma after getting shot on the job. When he wakes up, he finds that America has undergone a catastrophic change, and has transformed into a barren, zombie infested wasteland. Rick eventually meets up with a larger group of survivors, and the focus of the show transitions to the survival of the group as a whole. This is an excellent example of that rule, that zombie stories are about the people and their reactions to the zombies, not the creatures themselves. As such, both the two films I mentioned and The Walking Dead choose not the focus on the grand scheme of things, and instead stick to their established microcosms. None of these stories are about saving the world, or defeating the zombies. They are about survival, on a personal, individual level. I think this is part of what makes zombie stories so alluring; very few other stories, outside the post-apocalyptic genre, are told in this way, with the characters main goal being survival rather than victory. Dead Set, again, is a mini-series which chooses not to show us the bigger picture of the zombie infestation, but instead lets us glimpse it through the eyes of a small, isolated group of characters (in this show's case, they are the fictional participants and crew of Big Brother, a reality show). While Dead Set, like Shaun of the Dead, has many brilliant moments and ideas that I won't be discussing today, the main point to take away from it is that zombie stories are better when so many of the real details are left to the imagination.

Of course, as with every rule, there are exceptions. World War Z is a novel by Max Brooks that tells the history of the decade-long 'zombie war', a planet-wide conflict that humanity eventually triumphed in. The novel gives us plenty of details, shows us the big picture, the grand scheme, all of the things I've just said good zombies stories don't usually do. But somehow, it still succeeds. This, in my opinion, is down to the book's format. It bills itself as 'an oral history of the zombie war', because it consists of a series of interviews with survivors of the conflict. Government officials in America, human traffickers in Tibet, foot soldiers in Russia and doctors in China; all of these and more are interviewed and have tales to tell. Over the course of the novel, a solid, global picture of the apocalypse is built up; but it is done through the tales of those isolated individuals that make the genre what it is. Brooks also wrote, perhaps unsurprisingly, The Zombie Survival Guide; less of a story, more of a practical manual to fighting and defending against the undead. While it doesn't really have a story, you can still interpret the books instructions in parallel to the other zombie stories I've discussed. By that, I mean that the book is not aimed at restoring the world to its former glory or completely wiping out the undead. It is instead focused on keeping people - individual characters, you might say - alive. Though indirectly, even The Zombie Survival Guide follows this pattern.

There are some sources for zombie stories that I won't discuss today, for various reasons. Firstly is Warm Bodies, a novel by Isaac Marion. While it is an absolute joy to read and an excellent zombie story in its own right, it differs greatly from most other stories of this type because it is told from a zombie's perspective. This, and the fact that it offers and somewhat alternative version of the undead to what we are used to, means that it probably won't play a major role if I ever get round to compiling a proper zombie survival 101 post, which I eventually plan to do (if you want to know more about Warm Bodies, you can read the review I did for it last Halloween). I'm also not going to talk much about video game zombies as, while my two main sources of experience in this medium - Call of Duty's 'zombies' mode and Red Dead Redemption's Undead Nightmare expansion pack - are both great fun, they aren't really very story-heavy (the single player campaign in Undead Nightmare has a good plot to it, to be fair, but it is essentially a riff off of the original RDR cast of characters, and not really to be taken seriously).

I won't reiterate my point about individual struggles for survival as a conclusion, because I've probably already run that into the ground, so instead I'll just say that I'll start work on a proper, zombie survival post in the near future, and I hope you'll enjoy it when it's done. Thank you very much for reading this little slog through the zombie stories of the world, and please do go and check out any of the sources I've mentioned. Feel free to comment on this post if you liked it, or follow my blog, or follow me on Tumblr or Twitter, and so on and so forth. Until the next time, thanks again for reading!

Sunday, 25 March 2012

Preparing For Z-Day

Labels:

Books,

Dead Set,

Red Dead Redemption,

Shaun of the Dead,

The Walking Dead,

The Zombie Survival Guide,

Video Games,

Warm Bodies,

World War Z,

Zombieland,

Zombies

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

Sunday, 11 March 2012

Diminishing Returns

Ever since Doctor Who returned in 2005, it has been bringing back more and more villains and enemies from the classic series. For the most part, these recurring monsters have been handled well; the Daleks, though overused, are for the most part done brilliantly; the Sontarans are a vast improvement on their classic series counterparts, and I personally am absolutely in love with the RTD era's portrayal of the Master. However, there is one nemesis of the Doctor's who I think have been mishandled during the show's revived run; more specifically, his silver nemesis. The Cybermen have graced our screens no less than six times over the last seven years of Who, and each of those appearances, I think, has lacked the certain quality that makes the Cybermen the iconic and memorable villains that they are. That's what today's post is all about.

Our first glimpse of the new Cybermen was also the story that came the closest to restoring their 'alpha enemy' status; 2006's two-part adventure Rise of the Cybermen/The Age of Steel. This story is a near-miss, coming the closest to re-establishing the sinister cyborgs, but it trips up in a few vital areas. The Doctor, Rose and Mickey crash the TARDIS through a tear in the fabric of reality, ending up in a parallel universe where 'everything is the same, but a little bit different'. They quickly discover that this new world has its own breed of Cybermen; rather than the augmented, humanoid aliens the Doctor had encountered in the past, these were humans encased in machinery and cybernetics, devoid of emotion, manufactured by the malevolent Cybus industries. The story follows the Doctor and his companions - plus a ragtag group of freedom fighters - on their mission to shut down Cybus industries and stop the creation of these 'upgraded' humans.

As I said above, this story is definitely the strongest for the Cybermen in the new series, possibly because it was their re-introductory story and the DW team wanted the old villains to come back with a bang; their last appearance had been almost twenty years earlier, so many of the show's younger viewers would never have seen a Cyberman before. They appear in the story as threatening and intimidating, and the horror of their creation (a whirl of buzz saws and screaming) is sure to send a shiver down the watcher's spine. Unfortunately, the thing that makes this story so interesting is also its downfall for the Cybermen. These parallel world Cybermen are intriguing in the emotional dilemmas that they present, from Pete realising his wife has been converted to the Doctor defeating them by disabling their emotional inhibitors; but it's a one-shot deal, a clever take on a classic villain, but not one that can be repeated. There's no way of keeping these parallel Cybermen interesting after this initial story has fallen by the wayside, so all of the advantages that these episodes give them are too short-lived to be truly effective. While clever variations on the themes of this episode have appeared elsewhere - most notably in the Torchwood episode Cyberwoman - these ideas are few and far between. To really bring the Cybermen back to their former glory, they need to be given a firm base on which new and interesting ideas can be tested; by starting their new-Who run off with a unique take on them, rather than the definite article, the show left the Cybermen on shaky ground for future appearances.

But return these parallel Cybermen did, in the series two finale The Army of Ghosts/Doomsday. The Doctor and Rose return to present day Earth to find the streets being walked by 'ghosts' - but these blurred figures are not as serene as they seem, and are soon revealed to be Cybermen pushing across from their reality into ours. This time round the Cybermen themselves are less of the focus, as the story also has to deal with the departure of Rose and the return of another classic villain, the Daleks. As a result, the alternate Cybermen are slightly sidelined, and don't get any development or innovation as antagonists. While it isn't always necessary to do something completely different when an old enemy is brought back, this isn't the only problem the Cybermen have in this story. They also suffer at the hands (or plungers) of the aforementioned Daleks; for much of Doomsday, the two species are locked in combat with each other, and it doesn't take long for the Daleks to emerge as the clear victors. It doesn't do much for the Cybermen's status as major villains when we see them getting taken apart so thoroughly by just four Daleks. While it's obvious that the Daleks are a superior race, having it hammered home like that really knocks the reputation of the cyborgs.

The Cybermen then disappeared for a time, making not a single appearance throughout series' three and four. This long absence made their eventual return more effective - but unfortunately, the story they returned in did them no favours. The Next Doctor is really two stories in one; it follows the Cybermen as they attempt to unleash a dreadnought ship upon Victorian London, but it also unravels the mystery surrounding David Morrissey's eponymous character, a man claiming to be a future incarnation of the Doctor. The majority of this episode concerns discovering the truth behind this impostor, and the interactions between Tennant and Morrissey. Just like in Doomsday, the Cybermen become B-plot villains, filling up space and adding tension to a story that they don't quite belong to.

That was the last showing of the Cybermen for the RTD era; when the CybermenMoffat in series five's The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang. As the Doctor and Amy are exploring the underground chamber beneath Stonehenge, a battered, torn-up Cyberman guard advances on them. This is actually an extremely effective scene; the Cyberman's head, detached from the rest of the body, attacks Amy with tentacles of wiring and a snapping 'jaw', making for a scarier Cyberman scene than we've had in a long time. Sadly, though, that's all it is - a scene. Once again, the Cybermen are not the main focus of the story; they are one facet of the Alliance, a collaboration of the Doctor's greatest foes. More than once, Moffat has assembled multiple Who villains in a single story, and - while this generally lends the episodes involved a grand, epic feel - it lessens the impact that the villains can have. This comes across in the next appearance of the Cybermen, A Good Man Goes To War, where Rory sneaks onboard their ship in an attempt to gain some vital information. The Cybermen are shrugged aside almost instantly, in a story that also features Sontarans, Silurians and Judoon. Moffat's bombastic storytelling in that episode comes at the cost of the reputation of the Cybermen as A-grade villains.

The most recent story to feature the Doctor's silver nemeses was Closing Time, the penultimate story of series six. The Doctor, travelling alone, meets up with his friend Craig, and discovers that there are Cybermen hiding underneath a local department store. I wish I could say that this is where things turn around for the steel soldiers, but they are regrettably worse than ever. Between Craig's struggling relationship with his baby son Alfie (Stormageddon, Dark Lord of All!) and the Doctor contemplating his imminent death, there's barely any time left for the Cybermen to do much more than stomp around and look menacing. They get maybe ten minutes of screentime throughout the story, spending most of it confined to the background, leaving most of their monster duties to the pseudo-comical Cybermat. It's yet another example of a recurring problem throughout most of the stories I've discussed here; the Cybermen don't make the story. It could have been any other villain. With the exception of series two's parallel dimension stories, every episode to utilise the Cybermen in the new series would work just as well with any other villain. They don't put an iconic stamp on the stories they appear in, and are relegated to B-plot bad guys, playing second fiddle to other plot lines and characters. If they aren't allowed to preside over their own episodes, how are they supposed to re-establish themselves as the dangerous, threatening forces that the Doctor fought in days gone by?

This has been by no means a comprehensive look at the new Cybermen - I haven't talked about the various additions to their mythos such as Cybershades, for example - but, as an overview of why the Cybermen have been somewhat lacklustre in their recent showings, I think I've covered quite a few key areas. Thank you very much for reading, and feel free to leave a comment if you enjoyed what you read.

Our first glimpse of the new Cybermen was also the story that came the closest to restoring their 'alpha enemy' status; 2006's two-part adventure Rise of the Cybermen/The Age of Steel. This story is a near-miss, coming the closest to re-establishing the sinister cyborgs, but it trips up in a few vital areas. The Doctor, Rose and Mickey crash the TARDIS through a tear in the fabric of reality, ending up in a parallel universe where 'everything is the same, but a little bit different'. They quickly discover that this new world has its own breed of Cybermen; rather than the augmented, humanoid aliens the Doctor had encountered in the past, these were humans encased in machinery and cybernetics, devoid of emotion, manufactured by the malevolent Cybus industries. The story follows the Doctor and his companions - plus a ragtag group of freedom fighters - on their mission to shut down Cybus industries and stop the creation of these 'upgraded' humans.

As I said above, this story is definitely the strongest for the Cybermen in the new series, possibly because it was their re-introductory story and the DW team wanted the old villains to come back with a bang; their last appearance had been almost twenty years earlier, so many of the show's younger viewers would never have seen a Cyberman before. They appear in the story as threatening and intimidating, and the horror of their creation (a whirl of buzz saws and screaming) is sure to send a shiver down the watcher's spine. Unfortunately, the thing that makes this story so interesting is also its downfall for the Cybermen. These parallel world Cybermen are intriguing in the emotional dilemmas that they present, from Pete realising his wife has been converted to the Doctor defeating them by disabling their emotional inhibitors; but it's a one-shot deal, a clever take on a classic villain, but not one that can be repeated. There's no way of keeping these parallel Cybermen interesting after this initial story has fallen by the wayside, so all of the advantages that these episodes give them are too short-lived to be truly effective. While clever variations on the themes of this episode have appeared elsewhere - most notably in the Torchwood episode Cyberwoman - these ideas are few and far between. To really bring the Cybermen back to their former glory, they need to be given a firm base on which new and interesting ideas can be tested; by starting their new-Who run off with a unique take on them, rather than the definite article, the show left the Cybermen on shaky ground for future appearances.

But return these parallel Cybermen did, in the series two finale The Army of Ghosts/Doomsday. The Doctor and Rose return to present day Earth to find the streets being walked by 'ghosts' - but these blurred figures are not as serene as they seem, and are soon revealed to be Cybermen pushing across from their reality into ours. This time round the Cybermen themselves are less of the focus, as the story also has to deal with the departure of Rose and the return of another classic villain, the Daleks. As a result, the alternate Cybermen are slightly sidelined, and don't get any development or innovation as antagonists. While it isn't always necessary to do something completely different when an old enemy is brought back, this isn't the only problem the Cybermen have in this story. They also suffer at the hands (or plungers) of the aforementioned Daleks; for much of Doomsday, the two species are locked in combat with each other, and it doesn't take long for the Daleks to emerge as the clear victors. It doesn't do much for the Cybermen's status as major villains when we see them getting taken apart so thoroughly by just four Daleks. While it's obvious that the Daleks are a superior race, having it hammered home like that really knocks the reputation of the cyborgs.

The Cybermen then disappeared for a time, making not a single appearance throughout series' three and four. This long absence made their eventual return more effective - but unfortunately, the story they returned in did them no favours. The Next Doctor is really two stories in one; it follows the Cybermen as they attempt to unleash a dreadnought ship upon Victorian London, but it also unravels the mystery surrounding David Morrissey's eponymous character, a man claiming to be a future incarnation of the Doctor. The majority of this episode concerns discovering the truth behind this impostor, and the interactions between Tennant and Morrissey. Just like in Doomsday, the Cybermen become B-plot villains, filling up space and adding tension to a story that they don't quite belong to.

That was the last showing of the Cybermen for the RTD era; when the CybermenMoffat in series five's The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang. As the Doctor and Amy are exploring the underground chamber beneath Stonehenge, a battered, torn-up Cyberman guard advances on them. This is actually an extremely effective scene; the Cyberman's head, detached from the rest of the body, attacks Amy with tentacles of wiring and a snapping 'jaw', making for a scarier Cyberman scene than we've had in a long time. Sadly, though, that's all it is - a scene. Once again, the Cybermen are not the main focus of the story; they are one facet of the Alliance, a collaboration of the Doctor's greatest foes. More than once, Moffat has assembled multiple Who villains in a single story, and - while this generally lends the episodes involved a grand, epic feel - it lessens the impact that the villains can have. This comes across in the next appearance of the Cybermen, A Good Man Goes To War, where Rory sneaks onboard their ship in an attempt to gain some vital information. The Cybermen are shrugged aside almost instantly, in a story that also features Sontarans, Silurians and Judoon. Moffat's bombastic storytelling in that episode comes at the cost of the reputation of the Cybermen as A-grade villains.

The most recent story to feature the Doctor's silver nemeses was Closing Time, the penultimate story of series six. The Doctor, travelling alone, meets up with his friend Craig, and discovers that there are Cybermen hiding underneath a local department store. I wish I could say that this is where things turn around for the steel soldiers, but they are regrettably worse than ever. Between Craig's struggling relationship with his baby son Alfie (Stormageddon, Dark Lord of All!) and the Doctor contemplating his imminent death, there's barely any time left for the Cybermen to do much more than stomp around and look menacing. They get maybe ten minutes of screentime throughout the story, spending most of it confined to the background, leaving most of their monster duties to the pseudo-comical Cybermat. It's yet another example of a recurring problem throughout most of the stories I've discussed here; the Cybermen don't make the story. It could have been any other villain. With the exception of series two's parallel dimension stories, every episode to utilise the Cybermen in the new series would work just as well with any other villain. They don't put an iconic stamp on the stories they appear in, and are relegated to B-plot bad guys, playing second fiddle to other plot lines and characters. If they aren't allowed to preside over their own episodes, how are they supposed to re-establish themselves as the dangerous, threatening forces that the Doctor fought in days gone by?

This has been by no means a comprehensive look at the new Cybermen - I haven't talked about the various additions to their mythos such as Cybershades, for example - but, as an overview of why the Cybermen have been somewhat lacklustre in their recent showings, I think I've covered quite a few key areas. Thank you very much for reading, and feel free to leave a comment if you enjoyed what you read.

Labels:

A Good Man Goes To War,

Closing Time,

Cybermen,

Cyberwoman,

Doctor Who,

Doomsday,

Rise of the Cybermen,

The Age of Steel,

The Army of Ghosts,

The Next Doctor,

The Pandorica Opens,

Torchwood

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

Friday, 2 March 2012

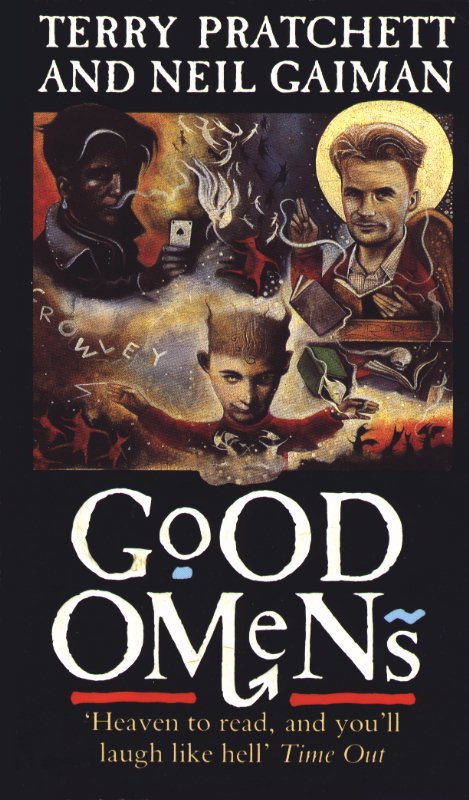

Good Omens

I've spent quite a lot of time reading the novel Good Omens, a collaboration between two brilliant authors, Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. I've mentioned my love of Gaiman before, in my review of his book Anansi Boys some time ago, and I've also enjoyed a couple of Pratchett's Discworld series. I wasn't aware that the two of them had ever worked together until very recently when I saw Good Omens on a bookshop shelf. I've read it mostly in short segments because I've been quite busy recently, but I finally finished it a few weeks ago and now I've decided to do a review of it.

I've spent quite a lot of time reading the novel Good Omens, a collaboration between two brilliant authors, Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. I've mentioned my love of Gaiman before, in my review of his book Anansi Boys some time ago, and I've also enjoyed a couple of Pratchett's Discworld series. I wasn't aware that the two of them had ever worked together until very recently when I saw Good Omens on a bookshop shelf. I've read it mostly in short segments because I've been quite busy recently, but I finally finished it a few weeks ago and now I've decided to do a review of it.The plot of the book chiefly concerns the coming of Armageddon. The son of Satan, the Antichrist, is born on Earth; however, due to a mishap at the hospital, Satan's son is given away to a normal family. Eleven years later, and 'Adam', son of Satan, is about to unknowingly unleash the apocalypse. The book follows several different characters, but Aziraphale and Crowley - an angel and demon respectively - are the chief protagonists. The two of them have both become comfortable with their lives on Earth, and as such (despite being polar opposites, good and evil), attempt to work together to avert the apocalypse. The story is also told from the perspective of Adam's gang, known as Them, and from that of the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

This being a Gaiman and Pratchett novel, the writing style is the thing that sticks in my mind the most. It is utterly fantastic; both authors have a very intelligent, long-winded way of structuring sentences that makes each and every line a pleasure to read. It's akin to a talented director shooting a film; not content with simply telling the story, the authors instead strive to find the most inventive, original and entertaining way to present the novel to the reader. This extra flourish of distinctive authorial style is what elevates a novel into the upper echelons of quality, and Good Omens is no exception.Gaiman and Pratchett go one step further, however, by adding a series of witty, tangential footnotes to the novel, that either expound upon incidental details or simply make clever jokes. The book is framed being 'based on the prophecies of Agnes Nutter' (a witch who predicted the events of the novel), with Gaiman and Pratchett acting as editors and compilers of the material. Whereas in any other novel the footnotes would break up the flow of the story and ruin the immersion for the reader, this framing device makes them seem natural and fitting to the story.

The novel's humour is another undeniably excellent factor. Obviously both of the authors have shown in other works that they know how to be funny - if any author can seamlessly blend fantasy and comedy, Pratchett can - but Good Omens takes their skills to new heights. Partly this is down to the diverse subject matter that the book is satirising; the wide range of subtle winks and nudges the novel gives to religious lore and legend adds another level to the humour, like an in-joke that the entire audience is in on. Things like Aziraphale misplacing the flaming sword from the Garden of Eden, or Pestilence (one of the four Horsemen) retiring and being replaced by Pollution, following the invention of penicillin. Of course, the book is also as hilarious as it is because of Gaiman and Pratchett's skill with dialogue. The exchanges between Crowley and Aziraphale are bursting with clever quips and one-liners, and several of the secondary characters are built around speech quirks that make even the most innocuous sentence a stand-out comedy moment (Witchfinder Shadwell's strong accent, for example, or Death speaking in all-caps).

However, while many of the minor characters do have comical traits as their defining characteristics, it doesn't mean that they aren't fully fleshed out as individuals. Each of the characters, even minor faces like the other members of Adam's gang, and the hell's angels, are given just enough characterisation to be likable, without their development bogging down the story. There's something in the way that the book describes and introduces these sideline characters that immediately endears you to them. Despite the ridiculous and often impossible nature of many of the characters, you can't help but sympathise with their problems and support their endeavours. That's not to say that the major characters don't pull their weight, though; I'm really not doing the book's diverse cast of characters justice in continuously referring to Crowley and Aziraphale in my examples, but I'm going to talk about them again now because they are the two who stick in my mind the most. On first introduction, the pair of them are little more than parodies of two famous biblical figures; Crowley is the serpent who tempts Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, while Aziraphale is the angel who guards the gates of the garden with a flaming sword - the book did start off life as a parody, after all. But slowly, as the novel deepens, we see past the satirical exteriors and get to know the characters. Aziraphale is a second-hand book dealer. Crowley's attitude to causing havoc is far too modern, and he is scorned by his outdated fellows because of it. The little things begin to add up, and before too long you realise, without consciously deciding it, you have fallen in love with this pair.

The plot of the novel is actually deceptively simple. Adam, son of Satan, has the power to accidentally cause the apocalypse. After he begins to unleash this power, very little happens in the way of plot twists or turns. The story is mostly focused on the various characters rushing to Adam, either to assist the beginning of the rapture or to prevent it. The complex nature of the novel instead comes from the multiple perspectives and presentation, with the writing style I mentioned earlier compensating where other stories might flounder. That's not to say it's a case of style over substance. On the contrary, the raising stakes of the ticking countdown to Armageddon provide the story with plenty of tension and drama, and you never reach a point in the story where the action lulls long enough for you to get even remotely bored.

I honestly couldn't say a bad thing about this novel if I tried. I've covered the writing, humour, characters and story and I still feel like I haven't said enough. I really can't recommend this one more. If you are a fan of Gaiman, buy it. If you're a fan of Pratchett, buy it. If you're a fan of comedy, buy it. If you're a fan of fantasy, buy it. Hell, if you're a fan of books, buy it.

So, that's me done for today, I think. I've recently been reading one of my favourite book series, the Tales of the Ketty Jay, which I definitely want to do a blog post about at some point, so watch out for that. In the meantime, I'm not sure what you should expect. I've not been posting as much recently for several reasons, but hopefully you'll see a bit more from me over the next few weeks. Until next time, thank you very much for reading - and feel free to leave a comment if you liked what you read. Goodbye!

Labels:

Books,

Good Omens,

Neil Gaiman,

Reviews,

Terry Pratchett

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

I do book reviews, talk about video games, write delightfully inconsequential works of fiction. And talk about Doctor Who a lot. Seriously, there's an outrageous amount of Doctor Who involved.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)